Ghost Towns of the North Shore

While Taconite Harbor, located near Schroeder, just might be the most well-known ghost town, it is far from the only one along Lake Superior’s North Shore. In fact, there are several dozen ghost towns dotting Lake Superior’s North Shore. Once thriving communities now lost to time and circumstance. These North Shore ghost towns tell the story of the past.

Many communities were formed because of industry, primarily minerals or lumber. Then, they ceased to exist when materials ran out or when government regulations limited their industry.

These communities came and then left leaving behind only memories. Here is the story of four such communities in Lake and Cook Counties that were once thriving communities. They were filled with families and homes that have since vanished, leaving little to nothing behind.

Forest Center, Lake County (Pictured Above)

In 1949 the Tomahawk Timber Company created the town of Forest Center along the southern shore of Lake Isabella in Lake County. The town was created to house employees of the nearby logging operations and mill. At its peak, the community was home to 250 residents and over 50 homes. The company also built a school, a restaurant, a coffee shop, a recreation hall, a general store, two churches, and a post office.

Located about 40 miles from Ely, the community was isolated from the rest of the world. Set deep in Minnesota’s Northwoods down unpaved roads that were scantly marked and could be difficult for an outsider to find. Because of this, it became a tight-knit community that has been described as “1950s suburbia, Northwoods style”. The community would come together on weekends for dances at the recreation center or a community baseball game. Most of the homes boasted white picket fences and a garden in the back.

Why It Became One of the North Shore Ghost Towns

Like many towns in the area, Forest Center was abandoned when the industry it was built on could no longer operate in the area. Because of its proximity to the BWCA, the Tomahawk Lumber Company found the area becoming greatly limited for logging operations. After logging more than 100,000 cords per year for 15 years, operations ceased in 1964. The residents of Forest Center moved on to other communities. Many of the homes and buildings were moved or demolished. Forest Center became a ghost town. Just a few signs that a once-thriving town once stood there remains. Mostly, the roads in town and a few foundations.

Reclaimed by Nature

The forest quickly reclaimed the area, making it nearly impossible to detect. In 2011, whatever relics were left of Forest Center were destroyed in the Pagami Creek Fire. The fire, however, cleared out some of the overgrowth once again revealing some of the foundations and other signs of the community. It would still take a knowledgeable eye to spot anything that was once a part of Forest Center, however. Even former residents who have returned say the area is unrecognizable to them.

These days, the Forest Center site is now a parking lot used for the Isabella Lake entry point for the BWCA and as the trailhead for the Powwow Trail. If you are ever in this lot for those purposes, take a look around. See if you can spot any signs of the North Shore ghost town of Forest Center.

Getting There:

Take Highway 1 from Highway 61 (near Tettegouche State Park). Turn right on Co Rd 7/Wanless Trail near the town of Isabella. Turn left on Trappers Lake Road. Stay on Trappers Lake Road for 5.8 miles and take a slight right onto Forest Road 173. After 2.9 miles turn left onto Forest Road 369. This road eventually becomes Forest Road 379. When the road ends, turn right onto Tomahawk Road. Look for signs for the Powwow Trail Head, turn into the parking lot. The town was located in this area. Please note that these are not paved road and not well marked. Some roads may even be completely unmarked. Please consult a map before heading out and ensure you know where you are going. Cell phone reception is not available here. A four-wheel-drive vehicle is recommended.

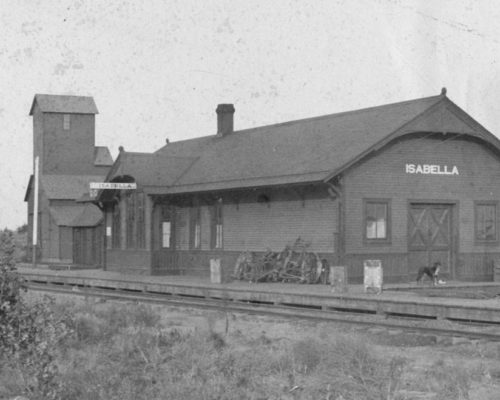

Sawbill Landing, Lake County

Forest Center was not the only community to spring up deep in the Northwoods during the 1940s lumber boom. There were more than half a dozen logging camps that dotted the northland during this time. Sawbill Landing is another one. Founded in the late 1940s, the town thrived for two decades. Then vanished.

In the case of Sawbill Landing, however, the community was not built by a lumber company. Rather, it was built by families who chose to create their own, independent town. They chose the landing area for the railroad where lumber would be transported to Lake Superior to be shipped out.

A Tight-Knit Community

These families created a lovely community. Sawbill Landing had a cafe, grocery store, gas station, post office, school, community center, and roughly a dozen homes. The school at Sawbill Landing taught the town’s children until 8th grade. In the early days, high school students from both Forest Center and Sawbill Landing would board in Ely for school. The roads between Ely and the area were often too treacherous to pass in the winter months. Then, in the mid-1950s the town of Silver Bay was founded along Lake Superior’s North Shore, and high school students were now close enough to be bussed daily.

The Beginning of the End

The town prospered for many years until 1964 when the first sign of trouble came. It all started with the school building burning down. In 1965 the BWCA boundaries were established and cut off part Sawbill Landing. Residents living in the portal zone were forced to move out. Finally, as the lumber industry slowed, so did the need for a railroad. The landing was closed. The rails were removed in 1970 and the remaining residents left with them. Sawbill Landing officially became another one of the North Shore ghost towns.

Like Forest Center, very little signs of the community exists today. Much of it has been reclaimed by nature. Those who once lived in the area can still detect traces of the community, but visitors would look upon the area and simply see the forest.

Getting There:

Follow directions to Forest Center, but instead of turning left onto Forest Road 369, continue on Forest Road 173. Take a slight right to stay on Forest Road 173. The town is located at the intersection of Forest Road 173 and Forest Road 174/Dumbell Road. Please note that these are not paved road and not well marked. Please consult a map before heading out. Cell phone reception is not available here. A four-wheel-drive vehicle is recommended.

Forest Center and Sawbill Landing Photos Courtesy of the Ely-Winton Historical Society

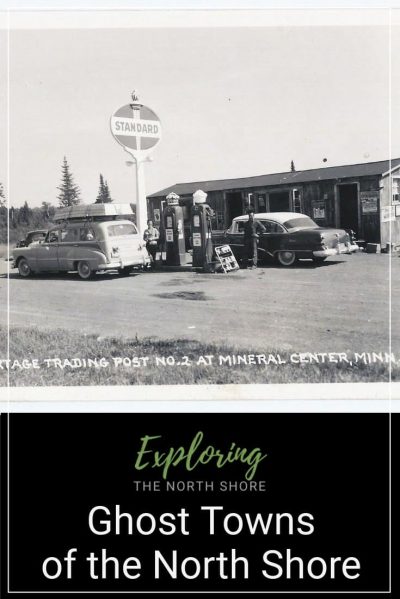

Mineral Center, Cook County (Pictured Above)

Before the logging rush of the 1940s, the area experienced the Mineral Rush at the turn of the century. In the 1880s and 1890s, settlers were attracted to the areas along Lake Superior’s shoreline further south near the communities now known as Knife River and French River. Then, with the passage of the Nelson Act in 1889, the land within the Grand Portage Indian Reservation to white settlers. The Mineral Rush moved north.

One of the most well-known settlements that was born during this time was Mineral Center.

A Family Endeavor

In 1909 Malcolm Linnell visited the area with family members from Black River Falls, Wisconsin. They came to see if the rumors of mineral deposits and rivers full of fish amongst the vast wilderness were true. What they found on their scouting mission was even greater than what they had expected. When they passed through Duluth on their way back to Wisconsin they filed their homestead claim on an area about 15 miles inland from Hovland.

The First White Settlers

In 1910 the first settlers who would eventually call Mineral Center home arrived in Hovland. Soon after, they started building their homestead. Despite some hardships early on. including wildfires that destroyed much of the surrounding area in 1913, Mineral Center survived and thrived. The community reached a population of around 350 by 1930.

Mineral Center would grow to have a post office, a general store, three schools, a church, and a cemetery. Interestingly, it was tourism that helped Mineral Center thrive. Visitors from Minneapolis and St. Paul would come up to experience a week in the wilderness. They’d go hunting for white-tailed deer, getting a ride on an ox-pulled cart, and hauling water from a nearby spring. Souvenir stands lined the main road where native artisans would sell their goods.

Mineral Center Becomes One of the North Shore Ghost Towns

Mineral Center’s eventual demise didn’t come as the result of natural resources drying up. They didn’t lose their primary industry and jobs the way other towns in the area had. Instead, Mineral Center became one of the North Shore ghost towns due to the Federal Government purchasing the homesteads back and returning them to the Grand Portage Tribe in 1940.

Eventually, the buildings and homes in Mineral Center were moved to other communities or dismantled for scrap wood. While Mineral Center itself became a ghost town, not all was lost! The cemetery was preserved and in 2010 a renovation was undertaken to ensure the cemetery would remain and the area still open to visitors.

Watch Mineral Center: Passport Into the Past by the Cook County Historical Society.

Getting There:

Take Highway 61 and turn onto Co Rd 89/Old Highway 61 a few miles north of Hovland, MN. Stay on Old Highway 61 for 6.3 miles until the intersection of Old Highway 61 and Co Rd 17/Mineral Center Road. The town and cemetery are located near this intersection on the Grand Portage Reservation. While these are maintained roads, they can be difficult to pass in poor weather. Please use caution and be aware of your route ahead of time. A four-wheel-drive vehicle is recommended.

Mineral Center photos courtesy of the Cook County Historical Society

Chippewa City, Cook County

This next North Shore ghost town is probably the easiest one to get to and see. Drive through the town of Grand Marais and right as you are leaving town, you’re there. Chippewa City was a thriving little village founded in the 1880s. By the 1890s it was home to about 100 families and growing.

There are a few well-known residents of Chippewa City that North Shore visitors will likely recognize the names of. John Beargrease, made famous for his mail delivery route and subsequent sled dog race that bears his name, lived here with his family. Then, artist George Morrison was born in Chippewa City in 1919.

The Struggles of Chippewa City

Like other North Shore towns, many thought Chippewa City would continue to thrive for generations. However, the town’s population started to dwindle in 1901.

It started when Highway 61 was expanded past Grand Marais, causing the removal of several homes and significant loss of land to the highway. A second blow came in 1907. That year, a fire destroyed several more homes. Luckily, the newly built St. Francis Xavier Church was spared thanks to sailors from a government boat that came ashore to fight the flames. The church was the pride and joy of the community, and still stands today. The 1918 flu epidemic also hit the community hard. Finally, the Great Depression found even more families leaving the area.

All of this eventually leads to Chippewa City becoming a ghost town. By the late 1930s, none of the original residents remained.

Not Entirely Lost to Time

Luckily, this is not one of the North Shore ghost towns lost entirely to time. In fact, one building still exists and you can actually still go inside of it!

According to the Historic Cook County website, the St. Francis Xavier Church was built in 1895 under the direction of Father Joseph Specht. The building was built in the French style by Ojibwe carpenter Frank Wishkop of hand-hewed, dovetailed timber. It served as the only Catholic church in the Grand Marais area until 1916 when St. John’s was built in town.

As the population of Chippewa City slowly diminished, so did the use of the church. Its final mass was conducted on Christmas 1936. The building sat mostly empty and unused for 2 decades. Then, in 1958 efforts began to restore the building with the Lions and the Catholic Church working together in the restoration process. In 1998 the church was donated to the Cook County Historical Society. It is on the National Register of Historic Places. During the summer months, you can visit it! They have it open for a few hours in the afternoon on weekends during peak season (May through September or October).

Chippewa City Cemetery

There is also a historic cemetery that still exists setback from Highway 61. Sadly, the “old side” of the cemetery is on the east side where most of the markers have been lost to time or removed due to being irreparably damaged, with little thought given to preservation. A few headstones remain, however they are difficult to read.

In recent years there have been some efforts made to identify the location of those buried in this part of the cemetery and to chart out the plots. This chart is on display in the church. Plans to renovate the cemetery have been ongoing for several years with little progress made.

Now Part of Grand Marais

While Chippewa City is no longer there, the area is still inhabited. Homes and cabins once again dot either side of Highway 61. The Cook County Home Center now sits where the community once was. It is considered part of Grand Marais.

Watch Chippewa City: Passport Into the Past by the Cook County Historical Society. Listen to WTIP’s Walking the Old Road series on Chippewa City. You can also learn more about Chippewa City in Staci Lola Drouillard’s book “Walking The Old Road: A People’s History of Chippewa City and the Grand Marais Anishinaabe”.

Getting There:

Chippewa City is located along Highway 61 about 1 mile northeast of Grand Marais. You will see the church on the lakeside of Highway 61.

More North Shore Ghost Towns

If you find this sort of history fascinating, we recommend checking out the book “Minnesota’s Lost Towns Northern Edition” by Rhonda Fochs. Rhonda’s “Lost Towns” series covers the rise and fall of hundreds of communities from all over Minnesota with her “Northern Edition” focusing on the northern half of the state, which includes St. Louis, Lake, and Cook Counties.

Also, visit the Cook County Historical Society website, or the museum in Grand Marais, to learn more about the North Shore’s lost communities.

There are dozens of towns, each with its own unique story to tell, that have been lost to time in the area. Other North Shore communities include Cramer, Illgen City, and Section 30 in Lake County and North Cascade, Parkersville, and Pidgeon River in Cook County- all of which are covered in Foch’s book.

The Ely-Winton Historical Society is a wealth of information for lost towns in the Lake County and Ely areas.

Listen to the North Shore Ghost Towns episode on the Exploring the North Shore Podcast: