SS Edmund Fitzgerald

“The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down, of a big lake they call Gitche Gumee. The lake, it is said, never gives up her dead, when the skies of November turn gloomy.” These are the poignant opening lyrics to Gordon Lightfoot’s 1976 hit song “Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”. The SS Edmund Fitzgerald is a doomed Great Lakes freighter that sank to the bottom of Lake Superior on November 10th, 1975 with all 29 men on board.

The loss of the ship was tragic to Great Lake Shipping in more ways than one. To understand the importance of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald to Great Lakes history, we need to go back another 17 years.

A Historic Iron Ore Freighter

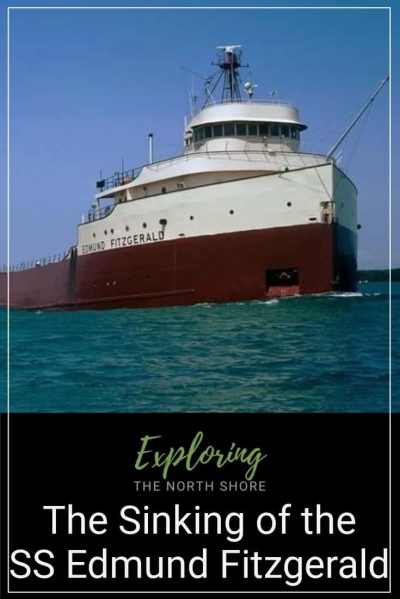

The SS Edmund Fitzgerald made history on June 7th, 1958. This was the day she made her inaugural trip on the Great Lakes. Measuring in at 729 feet long, “The Fitz” was the largest ship to sail the Great Lakes at that time. She became known as the “Pride of the American Side”. Her existence was a sign of post-Great Depression progress for the iron ore shipping industry. To the people of the Great Lakes, she was a symbol that all was once again right with the industry.

The Fitz was a spectacle! Visitors would often flock to the Duluth Harbor to see her coming and going. They just wanted to catch a glimpse of the “giant” ship. Duluth was her home as she sailed between the Twin Ports and other port towns, primarily Detroit.

The Gales of November

In the early years of the shipping industry, sailors learned a deep respect for the Great Lakes. Especially, for the storms that could suddenly erupt around them. The Mataafa Storm of 1905 and The Great Lakes Storm of 1913 each sank 11 vessels in a single day. Both storms happened in November during weather systems referred to as “The Gales of November“. The gales are said to “test the hulls of ships and the souls of men”.

However, by the time the SS Edmund Fitzgerald set sail, improved ship designs, modern radar navigation, reliable weather forecasting, and steady communication on the Great Lakes greatly reduced the number of shipwrecks. So much so, there hadn’t been a shipwreck on Lake Superior since 1953 when two freighters collided in heavy fog near Thunder Bay, Ontario.

So, when the SS Edmund Fitzgerald left port on November 9th, 1975, she did so with little hesitation. Despite the crew knowing of an impending storm system due to hit Lake Superior in the next couple of days, she sailed on. Those on board carried on as usual. It was to be her last voyage of the season.

The ship met up with the SS Arthur M. Anderson around 5PM that evening, just as the storm started passing by.

The Storm of the Decade

Early the next morning, Lake Superior was starting to show her fury. With her experienced Captain Ernest M. McSorley at the helm and a knowledgeable crew on board, the ship sailed on. They knew Fitz could withstand the storm. She was built to handle the elements and the forecast had predicted the storm to pass by 7 AM. Still, the SS Edmund Fitzgerald and the SS Arthur M. Anderson decided to be safe and altered their course to use the Ontario shoreline. Doing so would help them avoid most of the storm, which was expected to hit further south.

It would have been a good plan if the storm that done had done as predicted. But, Lake Superior decided to prove just how unpredictable she could be that day. Instead of passing by, the storm grew.

By mid-afternoon on November 10th, the combination of the high winds and waves and heavy snowfall caused the Anderson to lose sight of the Fitz. The Fitz had pulled ahead of the Anderson by several miles. However, the two ships continued to have radio contact.

The Growing Threat

Around 3:30 PM, Captain McSorley alerted Captain Jesse B. Cooper of the Anderson that the Fitz had started to take on water. The great ship was beginning to list. He made the decision to slow the Fitzgerald down to allow the Anderson to close the gap between the two so the ships.

The storm, meanwhile, continued to grow. It would come to have sustained winds of 58 MPH with gusts up to 86 MPH. Some of the biggest gusts ever reported on Lake Superior were recorded that night.

As the storm grew, the Captains made the decision to seek shelter in Whitefish Bay in Michigan until they could continue on safely.

The SS Arthur M. Anderson would make it to Whitefish Bay. The SS Edmund Fitzgerald would not.

The Sinking of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald

Just an hour after they first reported taking on water, the Fitzgerald’s radar failed. As the Anderson easily moved toward safety the Fitz stumbling along. The ship was essentially blind from the loss of radar. At 7:10 PM Captain Cooper asked Captain McSorley how the ship was doing. “We are holding our own,” was the reply. That was the last communication anyone would have from the Fitzgerald and her crew of 29.

After the Anderson reached White Fish Bay safely, it became clear that something had happened to the Fitzgerald. No distress call had gone out, but radio communication had ceased. There were no reported sightings of the Fitzgerald by the Coast Guard. At 9:03 PM Captain Cooper had to report the Fitzgerald as missing.

Attempted Rescue

The Anderson, under the request of the US Coast Guard, left the safety of White Fish Bay and went back out into the storm to search for the missing freighter. By 10:30 PM the Anderson was joined by the SS William Clay Ford. Other ships attempted to assist in the search efforts but were unable to due to the storm.

Despite great efforts in the search, the SS Edmund Fitzgerald was gone. All 29 onboard, gone with her. There were no survivors and no bodies ever recovered.

The Cause of the Sinking

The true cause of the sinking of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald has never been determined. It is clear that the unpredictable winter storm that hit Lake Superior on November 10, 1975, played a hand in her demise. However, the ship had faced similar storms in the past. She was built to withstand them.

Numerous theories have been proposed, including that the ship had unknowingly run aground while seeking refuge along the Canadian coastline, that a series of rogue waves known as “The Three Sisters” had overloaded the deck with water, and that the Fitzgerald itself was not as structurally sound (and was carrying a load far too heavy) as it was believed to be. While theories abound, the true cause will likely never be known.

Commemorations

In 1995, 20 years after it went to the bottom of Lake Superior, the ship’s bell was pulled from the wreckage. The bell was given to the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society. It now serves as a memorial for the 29 men who lost their lives. The bell can be seen at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Paradise, Michigan.

Meanwhile, back in Minnesota, the sinking of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald is commemorated every year on November 10th with the lighting of Split Rock Lighthouse. A small ceremony reading off the names of the crew members to the tolling of a ship’s bell is apart of the evening’s activities. This is the only opportunity visitors have to go into the lighthouse after dark and see the lit beacon.

The Last Maritime Tragedy on Lake Superior

The SS Edmund Fitzgerald was the last iron ore ship to sink in Lake Superior. It is also the largest ship to have ever met its end at the bottom of one of the Great Lakes to this day.

The sinking was, perhaps, made even more famous thanks to the song “Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” by Gordon Lightfoot in 1976. Lightfoot claims to have written the song as a show of respect for the men on board the Fitzgerald. His lyrics “Does anyone know where the love of God goes, when the waves turn the minutes to hours? The searchers all say they’d have made Whitefish Bay if they’d put fifteen more miles behind her,” describe how truly perilous those final minutes were for the ship, and just how close she came to safety.